Open/Closed Principle

One of the most common interview questions I have been asked is some version of “What does SOLID stand for and what does each principle mean?” I know there are thousands of articles already covering this subject with dozens more probably being created each week, but I’m going to add to the pile anyway! We’re going to take a deeper look at what each of these principles mean, how they should be used, and why they are important.

What is Solid

- S stands for Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

- O stands for Open Closed Principle (OCP)

- L stands for Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

- I stands for Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

- D stands for Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Background

You should read my posts on the other SOLID principles for a good understanding.

- Single Responsibility Principle

- Open/Closed Principle

- Liskov Substitution Principle

- Dependency Inversion Principle

Understanding the Open/Closed Principle

OCP states that every software entity should be open for extension, but closed for modification. The idea here is that once an entity is completed it should only be modified to fix bugs. If you want to add functional changes such as new features then you should be creating new entities.

What is a “Software Entity”?

In this definition a software entity is described as a class, module, function, etc… which performs some “unit of work” or handles a responsibility. For our purposes I will refer to classes throughout the remainder of this post.

What Does “Closed for Modification” Mean?

Closed for modification means that once you have implemented the desired functionality in a class you should not have to alter the code within that class except to fix issues.

What Does “Open for Extension” Mean?

Open for extension means that, if needed, a class can be built upon to increase functionality. This can be done a myriad of ways, but the most common is through interfaces and inheritance; specifically through the use of the Strategy design pattern which we will talk about later in this post.

A Practical Demonstration

This may all be sounding very esoteric and wordy, but the point is that we should attempt to write code that doesn’t need to be changed every time the requirements change. We should attempt to get the code into a state such that we don’t need to make invasive changes to the whole system. We should be able to add the new behavior by adding new code and changing very little or no existing code. Let’s consider for a moment electrical outlet extensions.

One day someone must have looked at the standard dual-socket outlet and realized “I need this to do more!”. Well, they had two options. They could either rip apart the existing outlet and rewire it to link to an increased number of sockets, which would need to be done carefully every time the extended functionality was needed, or they could build something that extends the functionality of the hardware that was already in place. The latter option provides a cleaner, less dangerous, and more portable solution to the problem in comparison to the former. Now, if someone needs 3 sockets they just need to plug in an extension which has 3 sockets and if they need 10 they just plug in one that has 10. There’s no need to alter the existing outlet to meet the changing requirements. Adding functionality to your software should be just as clean and non-invasive.

How to Apply the Open/Closed Principle

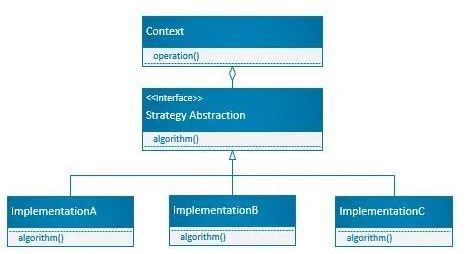

Abstraction is generally the way to realize this principle. Implementations of an abstraction are closed for modification because the abstraction is a fixed public contract, but the behavior can be extended by creating new implementations of the abstraction. If you’ve followed the first principle of SOLID (SRP) discussed here then your classes should already be separated into units of responsibility. These units can now be wrapped into abstractions. The consumers of this responsibility can then focus their attention on these abstractions rather than needing knowledge of any specific implementation. The use of abstraction to swap out an algorithm at runtime this way is called the Strategy pattern.

A Little More on the Strategy Pattern

The Strategy pattern is a design pattern which enables selecting an algorithm at runtime. By abstracting the logic we enable the consumer to be configured with an algorithm rather than implementing it directly. Take a moment to study the UML diagram below.

See it in Action

The code below shows a logging class which is directly dependent on internal knowledge of the implementation. For the sake of simplicity I have replaced the actual implementation for logging with a console message indicating where the message would be written to.

namespace SOLIDExamples.Loggers {

public enum LogType {

File,

Db,

EventViewer,

Console

}

public class BadLogger {

public void Log(LogType logType, string msg) {

switch (logType) {

case LogType.File:

Console.WriteLine($"Logging to file: {msg}");

break;

case LogType.Db:

Console.WriteLine($"Logging to DB: {msg}");

break;

case LogType.EventViewer:

Console.WriteLine($"Logging to Event Viewer: {msg}");

break;

case LogType.Console:

Console.WriteLine($"Logging to Console: {msg}");

break;

default:

Console.WriteLine($"Logger type is unidentifiable");

break;

}

}

}

}

There are a few things to take note of here.

- This class has 2 responsibilities. Logging and deciding how to log depending on the type. This breaks the Single Responsibility Principle.

- Because the logic of how to log the message is implemented within this class, if we needed to add a new methodology for logging (such as HTML) then we would need to change the inner workings of this class. This breaks the Open/Closed Principle.

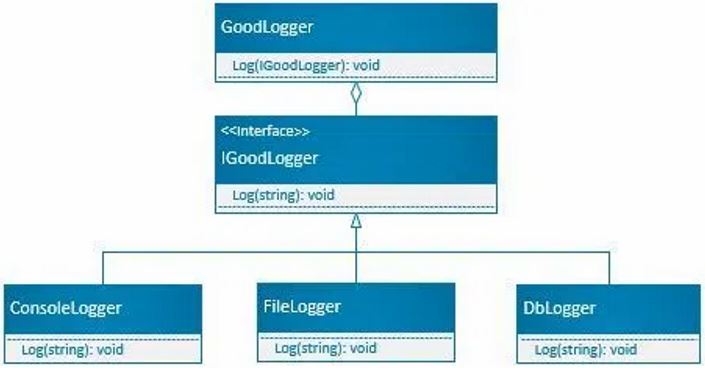

…So, how do we fix this? Well, remember the Strategy pattern? That’s right, it’s time to put it to good use. Let’s take a moment to visualize what our process would look like using this pattern.

Now that we can see what the code will look like, we can actually write it all down. Every methodology for logging is turned into its own class which implements a common interface. These classes are what will be used to construct the logger so that any actual implementation is now fully encapsulated.

namespace SOLIDExamples.Loggers {

public interface IGoodLogger {

void Log(string msg);

}

public class GoodLogger {

public void Log(IGoodLogger logger, string msg) {

logger.log(msg);

}

}

public class FileLogger : IGoodLogger {

public void Log(string msg) {

Console.WriteLine($"Logging to File: {msg}");

}

}

public class DbLogger : IGoodLogger {

public void Log(string msg) {

Console.WriteLine($"Logging to the DB {msg}");

}

}

public class ConsoleLogger : IGoodLogger {

public void Log(string msg) {

Console.WriteLine($"Logging to console: {msg}");

}

}

}

and the usage would be something like this:

var consoleLogTester = new ConsoleLogger();

var logger = new GoodLogger();

logger.log(consoleLogTester, "Test");

Now if we wanted to add a new logging methodology such as writing to the event viewer we could just add a new class like this:

namespace SOLIDExamples.Loggers {

public class EventViewerLogger : IGoodLogger {

public void Log(string msg) {

Console.WriteLine($"Logging to Event Viewer {msg}");

}

}

}

No need to worry about whether or not we accidentally broke something in the existing code because we don’t need to touch it.

When to apply the Open/Closed Principle

When I first learned this concept I began abstracting everything for every little task. After some experience I’ve come to realize that the need to ensure your class is open for extension is typically dependent on the context. If you have suspicions tha the requirements will soon change in a way that will require modification of the current code then it’s probably a good idea to prepare for that eventuality. However, we can’t always anticipate the needs of the future. I’ve found that it’s much better to focus my energy on writing code that is clean enough so that it’s easy to refactor when the requirements change. Requirements which change tend to continue changing in similar ways, so it is best applied to areas which are more likely to change. In the code example above, if the users requested the ability to log to the event viewer it doesn’t seem like too far of a stretch to think they’ll soon ask for the ability to log somewhere else as well. So, while it is definitely important to keep this in mind when designing your solution it is also important to remain balanced with more pragmatic concerns such as time and complexity.

Conclusion

As you can see from our example, the Single Responsibility and the Open/Closed Principles are extremely interdependent by nature. Keeping your classes small and separating concerns will inevitably lead to much cleaner code. We covered the Strategy pattern in this post as a way to apply OCP to your code, but there are a myriad of patterns which can be used for different scenarios. i will cover more design patterns in the future, but until then you should seriously consider reading Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software or Head First Design Patterns to learn more.