Liskov Substitution Principle

One of the most common interview questions I have been asked is some version of “What does SOLID stand for and what does each principle mean?” I know there are thousands of articles already covering this subject with dozens more probably being created each week, but I’m going to add to the pile anyway! We’re going to take a deeper look at what each of these principles mean, how they should be used, and why they are important.

What is Solid

- S stands for Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

- O stands for Open Closed Principle (OCP)

- L stands for Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

- I stands for Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

- D stands for Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Background

You should read my posts on the other SOLID principles for a good understanding

- Single Responsibility Principle

- Open/Closed Principle

- Liskov Substitution Principle

- Dependency Inversion Principle

Understanding the Liskov Substitution Principle

The Liskov Substitution Principle is an extension to Polymorphism. It states that, when using polymorphism, instances of the subtypes should be substitutable for the supertype without altering the correctness of that program.

Objects in a program should be replaceable with instances of their subtypes without altering the correctness of that program

What does that really mean? The simplest and most direct way I can think of explaining it that inheritance shouldn’t cause a change in behavior not meant by design. To get a better understanding let’s look at the pieces of the definition a little closer.

What is Polymorphism?

Often referred to as the third pillar of object-oriented programming, Polymorphism means “many forms”. This refers to the ability of an object to behave as multiple types depending on its inheritance. Objects of a derived class may be treated as objects of a base class at runtime; when this occurs the object’s declared type is no longer identical to its runtime type.

What is Inheritance?

Inheritance can be described as an “is-a” relationship. It is the ability to define a class in terms of another class. An example of inheritance is illustrated by the sentence: “A square is a rectangle”. In this example the square is inheriting the traits of the rectangle.

What is a Subtype?

A subtype is the child class in an inheritance relationship. In terms of the relationship “A square is a rectangle” the square is the subtype and the rectangle is the supertype.

What does “Correctness of the Program” Mean?

This means that the instance of the parent class can be replaced with an instance of the child class without affecting the results in a way that is outside the intended design. This is an important consideration for many reasons. The primary reason being that this excludes the typical inheritance usage, because the purpose of using the interface in these scenarios is to abstract multiple implementations. The intent is to alter the results when different types are used. So, an example of a rectangle implementing the interface IShape does NOT break this principle when the function Are is called for 2 reasons.

First, the rectangle class is the initial implementation of the area function. That is, there was no implementation for Area before the rectangle class was defined. This means that the initialization of an implementation is not the same as an alteration to existing logic.

The second reason is tightly coupled to the first. Because interfaces hold no implementation of their own, it was a designed intention for any implementing class to create that logic without constraint to any other implementation. This means that any logic Rectangle has which conflicts with other implementations is by design.

However, as we will see in our upcoming example, a Square class which extends rectangle can break this principle.

Example

Let’s say we have a system with the following requirements:

- Calculate the discount a customer receives based on their level of membership

- Add to the customer’s loyalty points depending on their level of membership

- The customer is either a silver or gold member

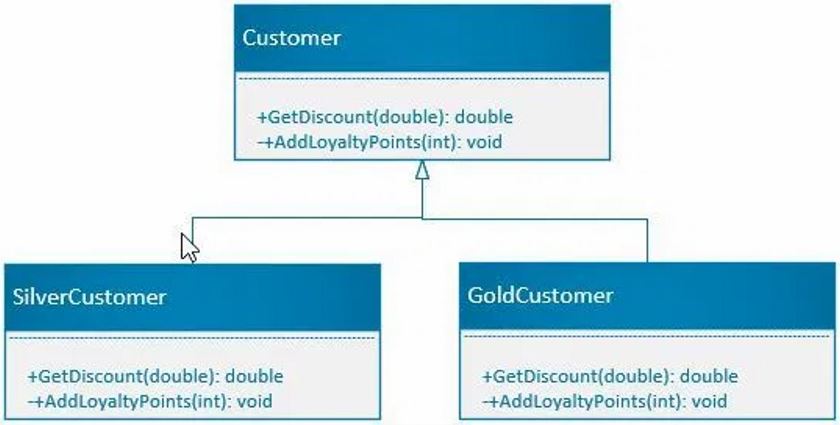

That would look something like what’s below.

public class Customer {

public virtual double GetDiscount(double totalSales) =>

return totalSales;

public virtual void AddLoyaltyPoints(int points) =>

Console.WriteLine($"Adding {points} points to customer's loyalty account");

}

public class SilverCustomer : Customer {

public override double GetDiscount(double totalSales) {

var total = base.GetDiscount(totalSales);

return total - (total * .25); // 25% off

}

public override void AddLoyaltyPoints(int points) =>

Console.WriteLine($"Adding {points} points to Silver customer's loyalty account");

}

public class GoldCustomer : Customer {

public override double GetDiscount(double totalSales) {

var total = base.GetDiscount(totalSales);

return total - (total * .5); // 50% off

}

public override void AddLoyaltyPoints(int points) =>

Console.WriteLine($"Adding {points} points to Gold customer's loyalty account");

}

Now, imagine that an additional feature has been requested. The client wants the ability to calculate the discount for people on their potential customers list a.k.a. “leads”. These individuals should not have loyalty accounts. So, following the Open/Closed Principle we add another class called Lead which inherits from the Customer class. Because a Lead has no loyalty account we override the AddLoyaltyPoints method to throw an exception. We should be good to go right? Take a look at the code below and see if you can figure out why this violates the Liskov Substitution Principle.

public class Lead : Customer {

public override double GetDiscount(double totalSales) {

var total = base.GetDiscount(totalSales);

return total - (total * .1); // 10% off

}

public override void AddLoyaltyPoints(int points) {

throw new Exception("Illegal Operation. Leads have no loyalty account");

}

}

So now we can use an instance of the Lead class as a Customer object thanks to Polymorphism.

Did you spot the problem? Let’s look at an example where we use these classes. What happens when we execute the code below?

var customers = new List<Customer> {

new Customer(),

new SilverCustomer(),

new GoldCustomer(),

new Lead()

};

foreach (var customer in customers)

customer.AddLoyaltyPoints(1);

As you may have figured out, the code above results in an exception because we attempted to call AddLoyaltyPoints() for an object of type Lead. If we remove the object from the collection then the code executes successfully. In other words, substituting the subtype Lead for the supertype Customer alters the correctness of the program by causing an exception to be thrown. This is clearly in violation of LSP.

How do we fix it?

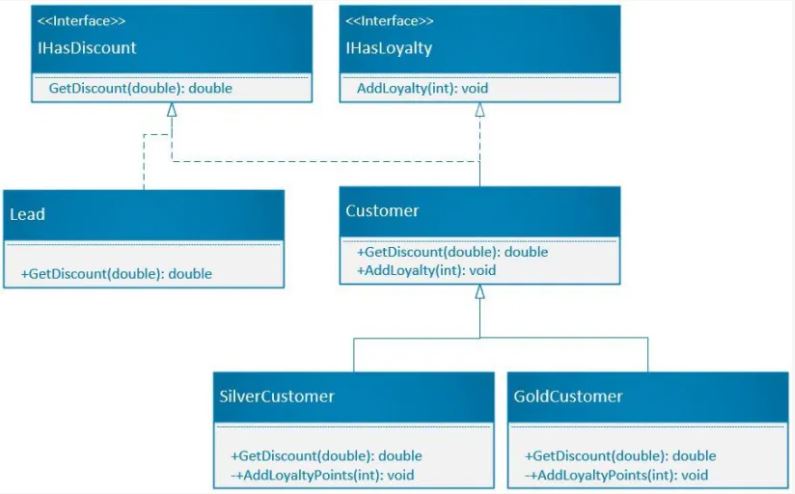

Separation of concerns. It’s pretty clear that when LSP is violated the subtype responsible is not as tightly related to the supertype as we initially thought. In this case, Lead is not actually a child of Customer. This makes sense at the business level because a lead is an individual who could potentially become a customer. By figuring out what the individual concerns or responsibilities are in these classes we can decide how to separate them correctly.

When we look at this example it becomes apparent that there are 2 main concerns.

- Having a discount

- Having a loyalty account

After a little contemplation it would probably become clear that neither of these two concerns are exclusive to customers. For example, an employee may have both a discount and a loyalty account. This means that we should probably decouple these concerns from the definition of a customer in our system anyway. In order to remove these concepts from any single definition we will create individual interfaces for each of them such as IHasDiscount and IHasLoyalty. Then we can pick and choose what our classes implement. After a little refactoring of the design it looks like this:

Creating the interfaces…

public interface IHasDiscount {

double GetDiscount(double totalSales);

}

public interface IHasLoyalty {

void AddLoyaltyPoints(int points);

}

Creating the Customer class and the subtypes…

public class Customer : IHasDiscount, IHasLoyalty {

public virtual double GetDiscount(double totalSales) =>

totalSales;

public virtual void AddLoyaltyPoints(int points) =>

Console.WriteLine($"Adding {points} points to customer's loyalty account");

}

public class SilverCustomer : Customer {

public override double GetDiscount(double totalSales) {

var total = base.GetDiscount(totalSales);

return total - (total * .25); // 25% off

}

public override void AddLoyaltyPoints(int points) =>

Console.WriteLine($"Adding {points} points to silver customer's loyalty account");

}

public class GoldCustomer : Customer {

public override double GetDiscount(double totalSales) {

var total = base.GetDiscount(totalSales);

return total - (total * .5); // 50% off

}

public override void AddLoyaltyPoints(int points) =>

Console.WriteLine($"Adding {points} points to gold customer's loyalty account");

}

Notice how the Customer class is an aggregation of both IHasDiscount and IHasLoyalty. Now either of these two interfaces can be used for the definition of additional unrelated entities, such as a Lead class.

public class Lead : IHasDiscount {

public double GetDiscount(double totalSales) =>

totalSales - (totalSales * .1); // 10% off

}

Now we have a proper separation of concerns. If we create a list of Customer or IHasLoyalty objects then we wouldn’t be allowed to add an instance of the Lead class. Functionality is consistent among the varying levels of inheritance and so LSP is upheld.

var loyaltyCustomers = new List<IHasLoyalty>() {

new Customer(),

new SilverCustomer(),

new GoldCustomer()

};

var discountCustomers = new List<IHasDiscount>() {

new Customer(),

new SilverCustomer(),

new GoldCustomer(),

new Lead()

}

foreach (var loyaltyCustomer in loyaltyCustomers)

loyaltyCustomer.AddLoyaltyPoints(1);

foreach (var discountCustomer in discountCustomers)

Console.WriteLine($"Discounted price for member level '{discountCustomer.GetType().Name}' is {discountCustomer.GetDiscount(100.5):N2}");