Interface Segregation Principle

One of the most common interview questions I have been asked is some version of “What does SOLID stand for and what does each principle mean?” I know there are thousands of articles already covering this subject with dozens more probably being created each week, but I’m going to add to the pile anyway! We’re going to take a deeper look at what each of these principles mean, how they should be used, and why they are important.

What is Solid

- S stands for Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

- O stands for Open Closed Principle (OCP)

- L stands for Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

- I stands for Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

- D stands for Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Background

You should read my posts on the other SOLID principles for a good understanding

- Single Responsibility Principle

- Open/Closed Principle

- Liskov Substitution Principle

- Dependency Inversion Principle

Understanding the Interface Segregation Principle

The Interface Segregation Principle states that interfaces should be small and contain only elements that are commonly required. This kind of functional grouping/isolation is right in line with our first principle: Single Responsibility. Where SRP applied to classes and methods, ISP applies to interfaces.

Clients should not be forced to depend on methods they do not use

What this means is that each implementation of an interface should only implement what it needs and nothing more. This reduces objects down to the smallest possible implementation, effectively reducing the dependencies the object doesn’t need for it t properly function.

How do we Spot the Issue?

One of the biggest code smells indicating a failure to follow ISP is throwing a NotImplementedException. If your class needs to pretend to implement a method to fulfill the contract of the interface then you have a problem.

Generally, if you are altering an interface without certainty that your change is desired by at least a majority (if not 100%) of the implementations then you want to look into different methods of correcting this issue.

How do we Fix it?

Break “fat” interfaces into multiple smaller interfaces and aggregate where needed.

A Simple Example

We are tasked with creating an interface for a calculator to add and subtract two numbers. So, we create the interface in the code section below.

public interface ICalculator {

double Add(double x, double y);

double Subtract(double x, double y);

}

This interface would have an implmentation like this:

public class Calculator : ICalculator {

public double Add(double x, double y) => x + y;

public double Subtract(double x, double y) => x - y;

}

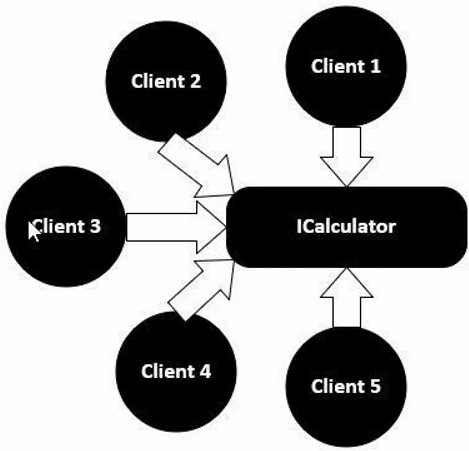

Now imagine that everyone loves the simple calculator interface and dozens of teams/clients are now implementing it.

After a while some clients decide that they really need the ability to do more than just add and subtract, they need to multiply and divide as well. The first thought would be “of course! That’s what calculators do, so we’ll add those methods to the interface”. Seems reasonable, but can you see the issue with the new definition of ICalculator?

public interface ICalculator {

double Add(double x, double y);

double Subtract(double x, double y);

double Multiply(double x, double y);

double Divide(double x, double y);

}

As you may have realized, this breaks the client base into two categories: people who wanted the multiply and divide functionality and those who did not. By fulfilling the request of a few clients this way you have disturbed the existing implementation of many currently happy clients. These clients now have to work around this undesired requirement which has been thrust upon them. Possibly forcing them to do something like this

public class Calculator : ICalculator {

public double Add(double x, double y) => x + y;

public double Subtract(double x, double y) => x - y;

public double Multiply(double x, double y) =>

throw new NotImplementedException();

public double Divide(double x, double y) =>

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

We could have instead extended ICalculator and added the requested methods to a new interface which clients can choose to implement if they want the functionality. That would look something like this:

public interface ICalculator {

double Add(double x, double y);

double Subtract(double x, double y);

}

public interface IComplexCalculator : ICalculator {

double Multiply(double x, double y);

double Divide(double x, double y);

}

public class Calculator : ICalculator {

public double Add(double x, double y) => x + y;

public double Subtract(double x, double y) => x - y;

}

public class ComplexCalculator : Calculator, IComplexCalculator {

public double Multiply(double x, double y) => x * y;

public double Divide(double x, double y) => x / y;

}

As you can see in the code section above, clients who do not wish to implement the new methods can continue using the original interface without being inconvenienced. On the other hand anyone who wishes to multiply or divide can implement the new interface instead.